Evaluation Report

Prepared for: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

Prairie Research Associates

500-363 Broadway

Winnipeg, MB, R3C 3N9

Phone: 204.987.2030 Fax: 204.989.2454

Toll-free (English): 1-888-877-6744

Toll-free (French): 1-866-422-8468

Email: admin@pra.ca

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry of Canada, 2023

Cat. No. CR22-66/2023E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-48425-9

PDF version (2.44 MB)

Table of Contents

Abbreviations

| CERCs |

Canada Excellence Research Chairs |

| CFI |

Canada Foundation for Innovation |

| CFREF |

Canada First Research Excellence Fund |

| CIHR |

Canadian Institutes of Health Research |

| CoR |

College of Reviewers |

| CRC |

Canada Research Chairs |

| CRCP |

Canada Research Chairs Program |

| DORA |

San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment |

| ECR |

early career researcher |

| EDI |

equity, diversity and inclusion |

| HQP |

highly qualified personnel |

| JELF |

John R. Evans Leaders Fund |

| IAC |

Interdisciplinary Adjudication Committee |

| LGBTQ2S+ |

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer or Questioning, and Two-Spirit |

| NSERC |

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada |

| SSHRC |

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council |

| TIPS |

Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat |

Executive summary

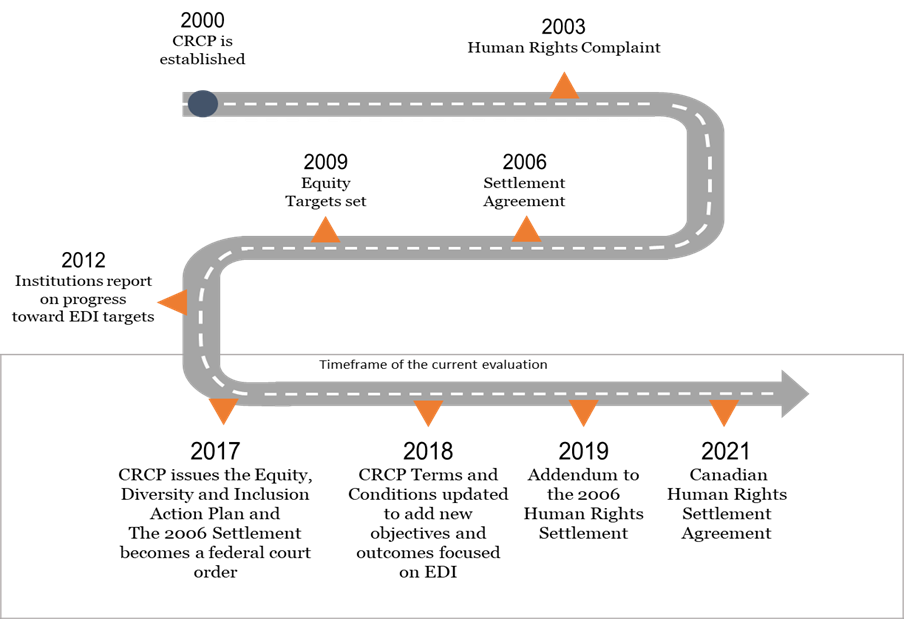

This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Canada Research Chairs Program (CRCP) that covered the period of April 2015 to March 2022. The purpose of this evaluation was to provide an assessment of the program’s relevance and performance, as well as aspects of design and delivery, including the implementation of equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) requirements.

Introduced in 2000, the CRCP supports 2,285 research professorships—Canada Research Chairs (CRCs)—in eligible degree-granting institutions across Canada. CRCs aim to achieve research excellence in engineering, natural sciences, health sciences, humanities and social sciences. The administration of the CRCP is the responsibility of the Tri-agency Institutional Programs Secretariat (TIPS), which is managed on behalf of the three granting agencies by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). The CRC award is an institutional grant that can be sought in combination with funding for research infrastructure from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Key findings

After more than 20 years since its implementation, the CRCP continues to play an important role in supporting research in Canada and the program’s objectives remain relevant. The program remained cost-efficient and performed well in terms of achieving its objectives. The findings from this evaluation show that the CRCP (including the accompanying CFI funding) continues to foster research excellence and capacity, as well as attract and retain a diverse cadre of excellent researchers to/in Canadian postsecondary institutions. However, during the period under evaluation, the COVID-19 pandemic created challenges that impacted the degree to which CRCs and their teams could complete planned research and the ability of institutions to attract international researchers.

Since the last evaluation, TIPS has implemented several changes to the design and delivery of the CRCP to further facilitate the program’s success in achieving its objectives. For instance, the Tier 2 stipend played an important role in attracting and retaining and in supporting CRCs in building research capacity. Limiting the number of renewals for the Tier 1 CRC award has provided opportunities for institutions to attract and retain new excellent researchers. Additionally, the implementation of new EDI requirements-particularly equity targets-has supported the attraction and retention of a diverse cadre of excellent researchers by helping the program and institutions identify, mitigate and reduce systemic barriers that prevent participation of members of designated groups.

However, certain CRCP design features are perceived to challenge the program’s success and present opportunities for improvement, some of which build on findings and recommendations from previous evaluations. Findings related to these features, as discussed in this report, led to the identification of three recommendations to help ensure that the CRCP continues to achieve its objectives through its support to CRCs and Canadian postsecondary institutions.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Investigate opportunities to increase the value of the Tier 1 and Tier 2 CRC awards with a specific emphasis on dedicating a minimum amount of funding for research.

One of the most notable areas for improvement recognized throughout the evaluation was the value of the CRC awards and the ways the funding is used by institutions: this was a persistent finding across most lines of evidence. CRC awards have approximately 53% less purchasing power now than in 2000 when adjusted for inflation and static funding over the last 20 years. This was perceived by stakeholders, institutional representatives and CRCs to have reduced the prestige and appeal of the award, making it less competitive for attracting international researchers and retaining excellent researchers in Canada. While the full extent to which the CRC award is used for attraction versus retention is unknown: the proportion of CRC awards used to attract researchers has consistently decreased over the 20 years of the program, and may continue to decline, in part, due to the value of the award.

Additionally, the majority of CRCP funds are used for CRC salaries, with approximately 21% of overall funds allocated for research-related expenses (e.g., student salaries, equipment, research stipends). As a result, financial resources to support the CRCs’ research programs are often provided through the institutional support package (not including the CRCP funds) or must be sought by CRCs through other funding sources. Such funding is critical to help CRCs build research capacity (e.g., hiring students). Without it, CRCs may be unable achieve their research goals and support the achievement of CRCP’s objectives.

The value of the CRC awards is a longstanding issue. The two previous CRCP evaluations recommended increasing the funding amount of the awards, possibly indexing to inflation. Increasing the value of the CRC awards and specifically dedicating funds for research provide an opportunity for the program to ensure the continued success of funded CRCs and the achievement of the CRCP’s objectives. While Budget 2018 announced additional funding for the CRC program, it was focused almost exclusively on the Tier 2 level: the number of chair positions was increased by 250 Tier 2 and 35 Tier 1, and a $20,000 research stipend was created for all Tier 2 chairholders during their first terms. While the Tier 2 CRCs’ research stipend is useful to help emerging researchers establish their research program, it may not be sufficient to offset the costs of their research. If the value of the CRC award is not increased, the CRCP may need to re-examine its objectives and the extent to which they can be achieved (e.g., attraction).

Recommendation 2: Examine opportunities to strengthen the support packages offered by institutions, including considering setting a minimum expectation for the financial and non-financial resources offered to CRCs across Canada.

The evaluation also found that the ways in which the CRC award funds are used vary within and across institutions. There are concerns that this will contribute to inequities across Canada. Similar concerns were observed throughout the evaluation in relation to the support packages institutions offer to CRCs. In addition to the CRC award, institutional support packages play a pivotal role in attracting and retaining excellent researchers and the success of a CRC’s research program. The financial and non-financial resources included in a support package are often left to the discretion of the faculty nominating the CRC, which results in wide variations in the supports offered and received by CRCs within and across institutions.

In certain cases, these supports are not competitive with what is offered by other Canadian or international institutions, nor are they robust enough to ensure the success of a CRC’s research program. While some CRCs were able to negotiate their institutional support packages at the time of nomination, others did not know this was a possibility. Additionally, some CRCs did not receive what was promised in their institutional support package and there is a perception among some CRCs that women experienced greater challenges when it came to their support packages, including receiving what was promised.

The quality and amount of supports offered by institutions to ensure the success of CRC research programs and the continued achievement of the CRCP’s objectives is an ongoing concern, noted in the previous evaluation. Setting a minimum standard of financial and non-financial resources institutions must offer as part of their support packages would provide an opportunity to level the playing field for CRCs across Canada, as well as increase the competitiveness and transparency of these packages. Changes to the requirements for institutional support packages should consider any changes to the value of the CRC award, as per recommendation one, and the impact such requirements may have on institutions.

Recommendation 3: Further clarify the definition and application of the concept of research excellence throughout the nomination and review processes, in alignment with the CRCP’s EDI requirements.

Since 2000, the CRCP has been successful at identifying excellent researchers through its nomination and review processes. While the CRCP has made progress towards integrating EDI into its nomination and review processes (e.g., unconscious bias training, equity targets), it was suggested that there is an ongoing preference for traditional measures of research excellence (e.g., the number and impact of peer-reviewed publications) that may not be conducive across contexts and do not necessarily reflect the quality and relevance of research. Additionally, some key informants, case study participants and institutions (through their EDI progress reports) expressed concerns that the focus on publication may disproportionally impact researchers who are members of the designated groups.

There is an opportunity for the CRCP to take a key role in clarifying the definition and application of the concept of research excellence and how it aligns with the program’s EDI requirements, particularly in the wake of the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) and the growing recognition of the value of using alternative measures of research excellence. For example, the program should develop additional guidance and training around less traditional research approaches and measures of productivity to support the individuals involved in the CRCP’s nomination and review processes. At the same time, it is important to recognize that defining and measuring research excellence is a broader issue within the research ecosystem, with implications beyond CRCP. It therefore requires the involvement of the three granting agencies. As evidenced in recent strategic plans and guidelines, the three granting agencies are examining and broadening the concept of research excellence. There may be opportunities for the CRCP to build on these efforts as the program continues to integrate EDI into its nomination and review processes.

1. Evaluation scope and methodology

This report presents findings from the evaluation of the Canada Research Chairs Program (CRCP). The evaluation reviewed the CRCP’s activities from April 2015 to March 2022 and was designed in adherence to the requirements of the Treasury Board’s Policy on Results (2016) and Section 42.1(1) of the Financial Administration Act, which requires that grants and contribution programs be evaluated every five years. Areas examined for this evaluation include the achievement of the CRCP’s expected outcomes and objectives, the extent to which the program’s objectives continue to be relevant, and the efficiency of the program’s design and delivery, including the implementation of equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) requirements. In the wake of the global pandemic, the evaluation also examined how COVID-19 affected the CRCP, as well as CRCs and their research programs. The CRCP was previously evaluated in 2015-16.

The evaluation was conducted jointly by the Evaluation Division of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), and Prairie Research Associates (PRA) Inc., an independent consulting firm specializing in program evaluation. Data was collected across multiple lines of evidence, including a review of program documents, key literature, program data, CRC annual reports, institutional annual reports and financial information, as well as from a comparative analysis. Data was also collected through:

- 45 key informant interviews with program stakeholders, unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP, and previous and reallocated CRCs;

- 10 case studies that involved a review of program data and key informant interviews with institutional representatives, CRCs and graduate students supervised by a CRC;

- a survey of institutional representatives (n=40); and

- a survey of Canada Research Chairs (CRCs) (n=1096).

The evaluation also leveraged the opportunity to include data from a student survey conducted as part of the evaluation of the talent-related programs of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), NSERC and SSHRC. Additionally, the Evaluation Division engaged in a contract with Elsevier Canada for a bibliometric and altmetric study of CRCs funded between 2009 and 2018 to assess their productivity, scientific achievements and impacts, compared to a control group of matched researchers and unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP. Data were analyzed by triangulating information gathered from the different lines of evidence listed above with the intention of increasing the reliability and credibility of evaluation findings and conclusions. See Appendix A for further details on the evaluation scope and methodology.

1.1 Evaluation questions

The evaluation examined the following themes and questions:

Relevance

- Is there a continued need for a program to attract and retain a diverse cadre of world-class researchers? (sections 3 and 5)

Effectiveness

- To what extent has the program fostered research excellence and developed research capacity? (section 4)

Efficiency

- What progress have institutions made in the implementation of the program’s EDI requirements? (section 6)

- To what extent does the CRCP design support the effective and efficient management of the program by TIPS and the implementation of the program by institutions? (section 7)

COVID-19

- What impact has the COVID-19 pandemic had on the delivery and performance of the CRCP? (section 4.5 and other sections as relevant)

2. Canada Research Chairs Program

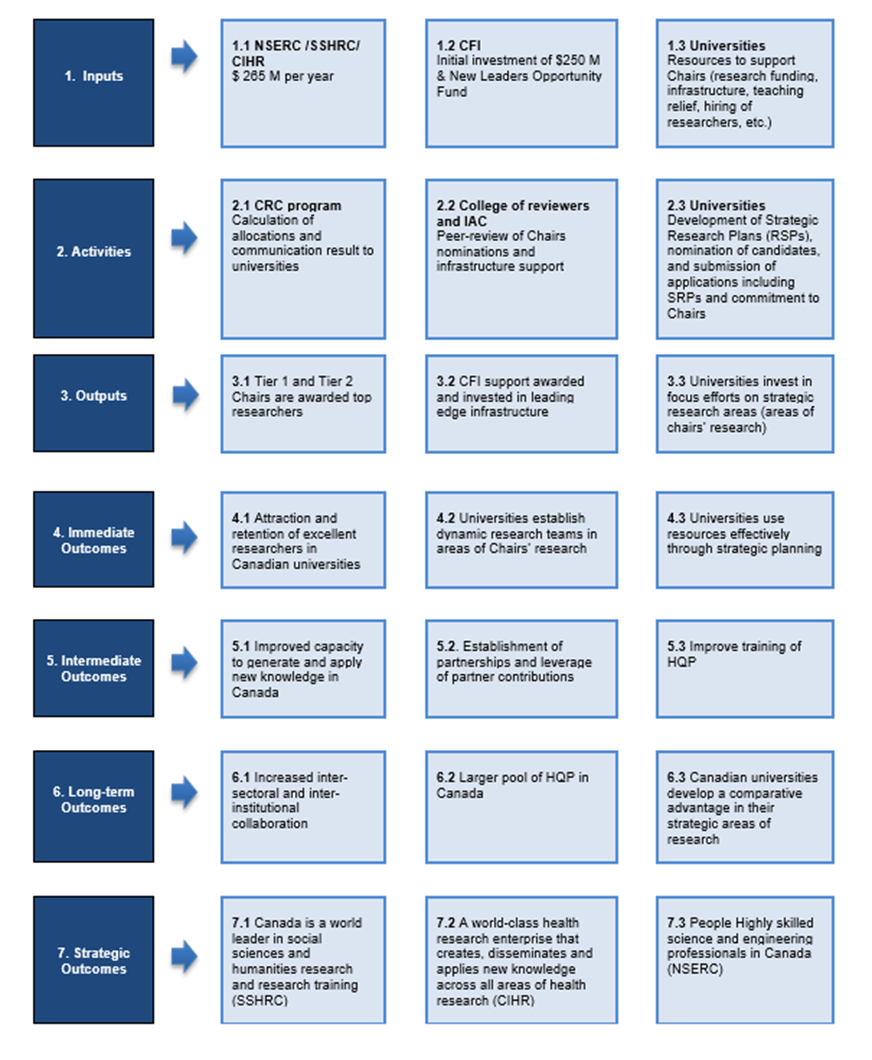

Introduced in 2000, the CRCP invests approximately $311 million per year to attract and retain a diverse cadre of some of the world’s most accomplished and promising minds to foster and reinforce academic research excellence and capacity in engineering and the natural sciences, health sciences, humanities and social sciences. The program is also committed to supporting a more equitable, diverse and inclusive Canadian research ecosystem and not perpetuating systemic barriers to the participation of individuals who are members of one or more designated groups, including racialized individuals, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities, women and gender minorities. The CRCP supports up to 2,285 CRC positions in eligible degree-granting postsecondary institutions (and their affiliate hospitals and research institutes), which represents approximately 4.8% of full-time academic positions across the country. CRCs improve our depth of knowledge and quality of life, strengthen Canada's international competitiveness, and help train the next generation of highly skilled people through student supervision, teaching and the coordination of other researchers' work. The logic model outlining the CRCP’s expected outcomes is found in Appendix B.

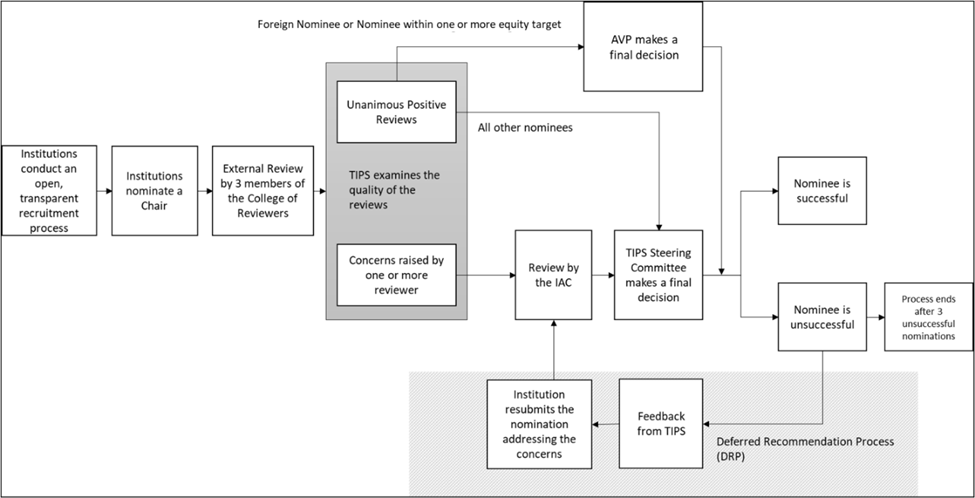

The administration of the CRCP is the responsibility of TIPS and is managed on behalf of the three granting agencies by SSHRC. The CRC award is an institutional grant and the number of CRC positions allocated to individual postsecondary institutions is proportional to the funding from the three granting agencies received by researchers at the institution over a defined period. The total number of CRC positions is divided across the three federal granting agencies with 837 awards (39%) dedicated to NSERC, 837 awards (39%) dedicated to CIHR, and 474 awards (22%) dedicated to SSHRC. There are also 137 special allocation CRC awards set aside for institutions that have received 1% or less of their total funding by the three granting agencies over the three years prior to the year of the allocation. These CRC awards are not allocated by granting agency and institutions can choose the areas in which they would like to use the CRC. Postsecondary institutions that have established their eligibility and have been allocated one or more CRCs are able to nominate researchers for available positions. Nominations are assessed by a minimum of three members of the College of Reviewers (CoR) through a rigorous multistage peer-review process to ensure that the nominated researcher meets CRCP’s evaluation requirements and high standards of research excellence. Additional details about the nomination and review processes are found in Section 7.8.

There are two types of CRCs funded through the CRCP. Nominees for a Tier 1 CRC are expected to be outstanding researchers who are acknowledged by their peers as world leaders in their fields. For each Tier 1 CRC, the institution receives $200,000 annually for a term of seven years that is renewable once. Nominees for a Tier 2 CRC are expected to be exceptional emerging researchers, acknowledged by their peers as having the potential to lead in their field. For each Tier 2 CRC, the institution receives $100,000 annually for a term of five years that is renewable once. Tier 2 CRCs also receive an annual $20,000 research stipend during their first term. When nominating a researcher for a CRC award, institutions are also able to apply for funding from the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) for infrastructure support to help acquire state-of-the-art equipment that is essential to the success of the nominee’s research program.

As of May 2022, there were 78 postsecondary institutions across Canada with active CRC positions and thus the ability to nominate excellent researchers to the CRCP. At the time of this report, 1,985 of the 2,285 CRC positions across Canada were filled, with almost two-thirds by Tier 2 CRCs (61%). Consequently, the vacancy rate for CRC positions was about nine percent (9%). This is close to the average proportion of vacant CRC positions between 2010-11 and 2020-21, which was approximately 14%. Institutions may have vacant CRC positions for several reasons, including delays between the ending of one CRC’s award and the beginning of another’s and keeping a position vacant in anticipation of the program’s reallocation process (discussed further in Section 7.5).

3. Continued relevance of the CRCP

CRCP stakeholders confirmed that the program’s key objectives―fostering research capacity and excellence; attracting and retaining a diverse cadre of excellent researchers; and supporting research that generates social, economic and cultural benefits―remain relevant 20 years after the program’s implementation. These objectives also continue to align with federal government priorities and departmental results for CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC. However, the emphasis placed on some objectives may have shifted over time, particularly in relation to notions of attraction and retention, research productivity and excellence, as well as EDI.

The CRCP was considered by many stakeholders to be a unique program due to its prestige, flexible funding, associated protected research time and reduced teaching requirements, as well as investment in an individual researcher and their research program for a longer period of time. CRCs are used by institutions to develop priority research areas and may act as a catalyst to develop research centres or clusters, some of which may be leveraged to seek and receive other prestigious tri-agency funding such as the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF) and Canada Excellence Research Chairs (CERCs). CRCs are also able to leverage the prestige associated with their award to receive additional grants to fund their research programs. Leveraging other funding is a necessity for CRCs because they often receive about a fifth or less of their award for research-related expenses, as many institutions primarily use CRCP funding for CRC salaries. In addition to accessing additional funding, the CRC award was noted by the majority of surveyed CRCs as having a positive impact on the quality and direction of their research and the creation and application of new knowledge. Interviewed CRCs indicated that the award provided opportunities to engage in collaborations and attract more and/or high-quality highly qualified personnel (HQP).

The CRCP’s key objectives are to enable eligible Canadian postsecondary institutions (and their affiliated hospitals and research institutes, as applicable) to:

- Foster research excellence and enhance their role in the global, knowledge-based economy as world-class centres of research excellence;

- Provide specific resources to help attract and retain a diverse cadre of world-class researchers and reinforce academic research excellence in Canadian postsecondary research institutions; and

- Support internationally competitive research and research capacity that generates social, economic and cultural benefits for Canada and Canadians.

The objectives of the CRCP are directly aligned with the federal government’s aim to hire more leading researchers and for Canada to be a leader in current and future economies to help generate economic growth for Canadians. The program’s objective of attracting and retaining a diverse cadre of excellent researchers and commitment to reducing systemic barriers to access and participation in the CRCP for designated groups also align with government expectations to continue address systemic inequities and disparities and ensuring that Canadians see themselves reflected in the government’s work and priorities. Finally, the CRCP’s objectives align with the departmental results for CIHR, NSERC and SSHRC, which expect that Canadian research in health, the natural sciences and engineering, and the social sciences and humanities is internationally competitive; that knowledge in these disciplines is used; that Canada has a pool of highly skilled people in the natural sciences and engineering, social sciences and humanities; and that Canada’s health research capacity is strengthened.

“It’s gone from being a bold new initiative to an important cornerstone of the Canadian research enterprise.”

—Key informant

Findings from the evaluation demonstrate that the CRCP continues to be necessary to support research in Canada and that its objectives remain relevant. Most program stakeholders and institutional representatives interviewed believe the need for the program still exists in the same capacity as when it was first implemented 20 years ago, and that its objectives continue to be relevant. Similarly, all institutional survey respondents indicated that the CRCP’s objectives remain relevant, the most relevant being enhancing the role of Canadian postsecondary institutions as world-class centres of research excellence (93%) and attracting a diverse cadre of excellent researchers (73%).

However, some key informants and case study participants noted that the emphasis on and expectations of the CRCP’s objectives may have shifted over time, particularly in relation to notions of attraction and retention, as well as research productivity and excellence. For instance, CRC awards appear to be increasingly used by institutions to retain excellent researchers. The CRCP and institutions also increasingly recognize new measures of productivity and research excellence. Some key informants highlighted the program’s increasing emphasis on EDI requirements and practices, particularly the equity targets that are focused on ensuring that the representation of CRCs in the program better reflects the Canadian population. Additionally, a small number of key informants, institutional representative survey respondents (8%) and case study participants felt that the CRCP was not meeting all its objectives. Reasons include the stagnant amount of the CRC award and the program’s inability to compete internationally in attracting excellent researchers. These changes in emphasis and expectations, as well as challenges in achieving the program’s objectives, will be discussed throughout this report.

Niche of the CRCP and synergies with other funding

Given the 20-years since the implementation of the CRCP, the program has become ingrained in Canada’s research ecosystem and is providing necessary foundational funding for institutions to allow them to foster research excellence and capacity. For example, because award alignment with an institution’s strategic research plan is expected and assessed as part of the review process, institutions often attach CRC awards to faculty positions of strategic importance to support priority research areas. Institutional representatives confirmed that the funding received through the CRCP allows their institutions to dedicate funds to developing priority areas and building research capacity in those areas, including clusters and/or centres. Since 2015, more than half of the institutions with CRCs indicated in their institutional annual reports that they place great importance on the CRCP as a catalyst to support existing research teams, research clusters and/or research centres at their institutions, with larger institutions placing a greater importance on the role of the CRCP. When asked if their institution has/had a research centre or cluster related to their area of research, almost two-thirds of surveyed CRCs (62%) said yes, with almost half of those CRCs (42%, n=492) indicating that their CRC award contributed to the creation of a research centre or cluster.

Evaluation participants noted that having CRCs, as well as research capacity and clusters in strategic areas of research, provides institutions with the ability to seek and receive other prestigious tri-agency funding, such as a CFREF grant. It was further noted that CRCs will often work as team members of a CFREF-funded project and with CERCs. The synergies between CRCs and other tri-agency funding are intentionally designed by institutions to further advance and accelerate research in areas of strategic priority to develop high-quality centres of research excellence and to increase Canada’s ability to be competitive internationally.

Program stakeholders, institutional representatives and CRCs spoke of the distinct nature of the CRCP compared to other funding programs offered by the granting agencies: this continues to make the program relevant in Canada. Among case study participants, the CRCP was viewed to be unique among federal programs due to its prestige, flexible funding, and the associated protected research time and reduced teaching requirements. Additionally, the CRC was considered to be distinctive by some key informants and case study participants because it provides funds for institutions to invest in an individual researcher and their research program, for a longer period of time. By providing researchers with a consistent funding base, they have more time to develop and achieve long-term research goal and support individual projects within that research program. Funding from the CRCP is perceived to be one leg of a three-legged stool, along with institutional support and other funding for research.

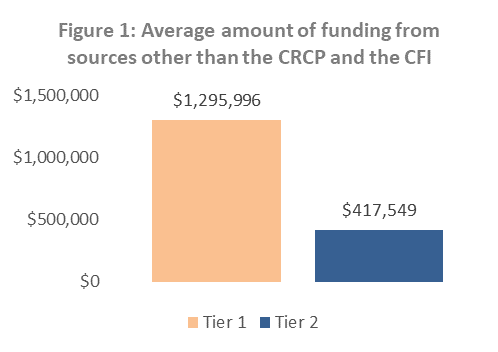

Individually, CRCs leverage the prestige associated with their award to seek additional funding to support their research programs. Many interviewed CRCs and institutional representatives explained that CRCs use funding from multiple sources (e.g., not-for-profit and private sectors, other federal grants) to maximize their research capacity. Data extracted from CRC annual reports from 2015 to 2020 show that CRCs are quite successful at securing funding from other sources. Tier 1 CRCs appear to be especially successful as they received, on average, $1,295,900 in funding from sources other than the CRCP and the CFI: this is about three time the average amount received by Tier 2 CRCs ($417,549) (see Figure 1).

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Description of figure

Figure 1: Average amount of funding from sources other than the CRCP and the CFI

| |

CRC Tier Level |

| Tier 1 |

Tier 2 |

| Average amount of funding from sources other than CRCP and CFI |

$1,295,996 |

$417,549 |

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Over three-quarters (77%) of surveyed CRCs agreed that the CRC award had a positive impact on their ability to obtain additional research funding from the federal government.

According to CRCs, the need for funding from multiple sources is also related to institutions’ primary use of CRCP funding for CRC salaries. Consequently, many CRCs receive about a fifth or less of their award for research-related expenses. While some CRCs noted their frustration with the time needed to write funding applications to be able to support their research, they often believe they are more successful at receiving additional funding because of their CRC title. This was indicated as another way in which the CRC award helps accelerate a CRC’s research program and ultimately their career. Such assertions were supported by findings from the CRC survey, which demonstrate that most CRCs (77%) believe the award had a positive impact on their ability to obtain additional funding from the federal government. The ability to combine CRC funding with other research grants was also highlighted by interviewed CRCs as an important attribute of the CRCP that helps build a research program.

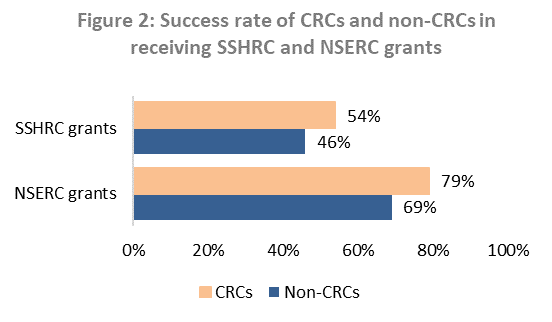

To verify the perception that CRCs are more successful at receiving federal funding, the success rate of CRCs and non-CRCs (i.e., researchers that have never held a CRC position) in receiving funding from certain SSHRC grants (Insight and Partnership grants) and NSERC grants (Alliance, Collaborative Research and Development, Discovery and Engage) was analyzed. As shown in Figure 2, CRCs were more successful in receiving these grants than non-CRCs, confirming this perception.

Source: NSERC and SSHRC program data

Source: NSERC and SSHRC program data

Description of figure

Figure 2: Success rate of CRCs and non-CRCs in receiving SSHRC and NSERC grants

|

Percentage of CRCs |

Percentage of non-CRCs |

| SSHRC grants success rate |

54% |

46% |

| NSERC grants success rate |

79% |

69% |

Source: NSERC and SSHRC program data

Improving research programs

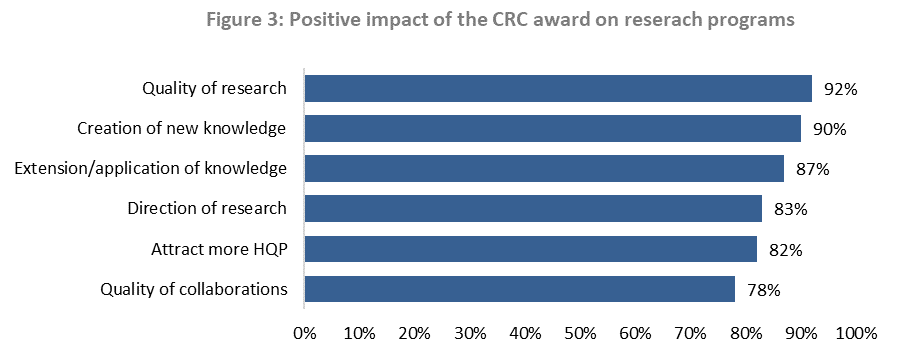

In addition to accessing funding, interviewed CRCs noted many other ways in which the CRC award improved their research programs, including increasing opportunities for national and international collaborations, and attracting high-calibre HQP. Measures of the positive impact of the CRC award on the quality and direction of research and the creation and application of new knowledge were also captured in the CRC survey, as shown in Figure 3. Several of the measures outlined in Figure 3 below are directly comparable to findings from the previous evaluation of the CRCP (quality of research, direction of research, attraction of HQP, quality of collaborations) and were either within 1 percentage point from 5 years ago or saw slight increases ranging from 2 to 6 percentage points.

Source: CRC Survey

Source: CRC Survey

Description of figure

Figure 3: Positive impact of the CRC award on research programs

| Ways in which the CRC award improved CRCs’ research programs |

Percentage of CRC survey respondents |

| Quality of collaborations |

78% |

| Attract more HQP |

82% |

| Direction of research |

83% |

| Extension/application of knowledge |

87% |

| Creation of new knowledge |

90% |

| Quality of research |

92% |

Source: CRC Survey

4. Fostering research excellence and capacity

4.1 Research productivity

Both traditional (e.g., bibliometric) and emerging (e.g., altmetric) measures of research outputs were used for this evaluation. As measured through publications, the bibliometric study showed that higher-quality (or excellent) researchers received the CRC award and continued to be excellent following their award: this suggests that the CRC award contributes to increased rates of publication. Although a slightly greater decrease in scientific impact for CRCs was found in comparison to the control group, the scientific impact of CRCs following the award remained above the world level. These findings are similar to those from the bibliometric studies completed for the last two evaluations of the CRCP, which continue to validate these processes.

An examination of alternative metrics found that CRCs increased their presence in social and traditional media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter and news media) before and after receiving their CRC award. However, only very small differences were observed between CRCs and the control group, which negated the confirmation of a clear positive effect of the CRCP on the presence of research generated by CRCs in social media. CRCs reported that they often engaged in knowledge translation with various sectors, the most common examples being presenting their findings to an external organization, participating in working groups, and sharing research results with the media.

Research publications

A bibliometric study was conducted as part of this evaluation: it examined the average number of research publications produced by individual CRCs during the period prior to and after receiving their award, and that of a matched control group of non-CRC researchers and unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP. However, note that as the population of researchers who were unsuccessfully nominated to a Tier 1 chair was rather small, the bibliometric indicators for unsuccessful nominees were only calculated and discussed for Tier 2 CRC award nominees. To ensure a successful match between the CRCs and researchers in the control group, their level of productivity in terms of publication and citation impact was similar by design. Researchers in the control group were also selected for the size of their affiliated institution and geographical location in order to align their research environment as much as possible. A final important note to consider when reviewing results from the bibliometric analysis is that, since close to half of the CRCP chairholders in the sample have NSERC chairs (45%), findings for the CRCP as a whole are largely due to/associated with those chairholders.

When moving from the pre-award period to the award period, the CRCs significantly increased their research output (across all three agencies), at a level that surpassed the increases observed for the control group and unsuccessful nominees. In particular, CRCs increased their research output from an annual average of 4.9 publications before the award to an annual average of 7.7 publications after their award. In comparison, the matched control group increased their annual research output from 4.6 to 5.7 publications on average, and the unsuccessful Tier 2 CRC nominees increased their annual research output from 2.2 to 4.0 publications on average (versus a change of 3.5 to 6.3 publications on average each year for Tier 2 CRCs).

Looking at comparisons among CRCs and unsuccessful nominees, findings from the study demonstrate that the average number of research publications produced by CRCs in the period before their award was significantly higher than the average number of research publications produced by unsuccessful nominees, indicating that the CRCP is selecting more productive researchers.

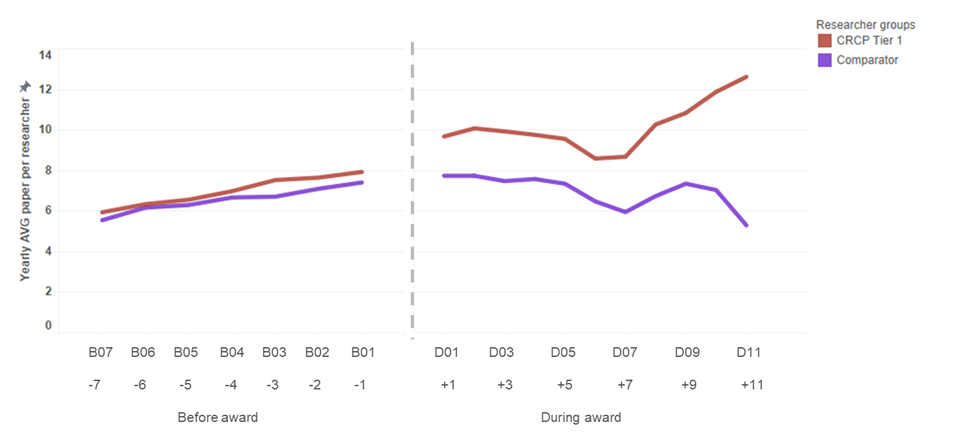

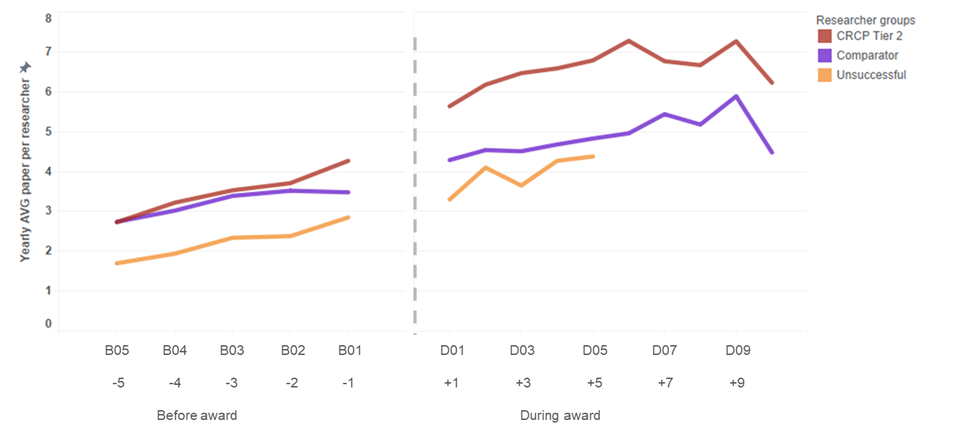

More simply, Figure 4 below presents the yearly average per group for Tier 1 CRCs in the periods prior to and during the award, while Figure 5 presents the same information for Tier 2 CRCs. As illustrated in Figure 4, before their award, the Tier 1 CRCs had very similar publication trends to the matched control group. In the period when CRCs were supported by their award, both groups experienced similar trends in their productivity for the first nine years; however, the productivity of CRCs was steadily higher. Additionally, by year 10 (after the start of their awards), the productivity of CRCs continued to increase while the publication rate of the matched control group began to decrease. During the five-year period before the award in Figure 5, the unsuccessful nominees increased their research output from 1.7 to 2.9 publications per researcher per year. At the same time, the control group and CRCs started at 2.7 publications to respectively reach 3.5 and 4.3 publications per researcher per year. During the award period, unsuccessful nominees reached a level comparable to that of the matched control group, although slightly lower. The CRCs had a substantially higher research output. Note, at the Tier 2 level, a stabilization-or a decrease-in the production of CRCs and the control group is observed for the later years. This is likely, at least in part, due to the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic as the yearly production of scientific papers decreased between 2019 and 2021 in Canada and across the world. The exact effect of COVID-19 is unclear as the research output is not aligned by calendar year but by number of years before or after receiving the award.

Figure 4: Trends in the annual average number of papers published by Tier 1 CRCs (before receiving support and up to 11 years with support), control group researchers and unsuccessful nominees

Source: Bibliometric study

Source: Bibliometric study

Description of figure

Figure 4: Trends in the annual average number of papers published by Tier 1 CRCs (before receiving support and up to 11 years with support), control group researchers and unsuccessful nominees.

| Before the grant (up to 7 years) |

CRC Tier 1 |

Comparator |

| B07 |

5.92 |

5.55 |

| B06 |

6.34 |

6.16 |

| B05 |

6.55 |

6.29 |

| B04 |

6.97 |

6.67 |

| B03 |

7.55 |

6.71 |

| B02 |

7.65 |

7.09 |

| B01 |

7.93 |

7.41 |

| During the grant (up to 10 years) |

CRC Tier 1 |

Comparator |

| D01 |

9.67 |

7.72 |

| D02 |

10.07 |

7.72 |

| D03 |

9.93 |

7.48 |

| D04 |

9.75 |

7.59 |

| D05 |

9.55 |

7.33 |

| D06 |

8.57 |

5.95 |

| D07 |

8.64 |

5.95 |

| D08 |

10.24 |

6.76 |

| D09 |

10.83 |

7.36 |

| D10 |

11.79 |

7.05 |

| D11 |

12.64 |

5.29 |

Figure 5: Trends in the annual average number of papers published by Tier 2 CRCs (before receiving support and up to 11 years with support), control group researchers and unsuccessful nominees

Source: Bibliometric study

Source: Bibliometric study

Description of figure

Figure 5: Trends in the annual average number of papers published by Tier 2 CRCs (before receiving support and up to 11 years with support), control group researchers and unsuccessful nominees.

| Before the grant (up to 7 years) |

CRC Tier 2 |

Comparator |

Unsuccessful |

| B05 |

2.74 |

2.74 |

1.69 |

| B04 |

3.22 |

3.03 |

1.93 |

| B03 |

3.53 |

3.40 |

2.32 |

| B02 |

3.71 |

3.52 |

2.37 |

| B01 |

4.28 |

3.48 |

2.85 |

| During the grant (up to 10 years) |

CRC Tier 2 |

Comparator |

Unsuccessful |

| D01 |

5.64 |

4.30 |

3.27 |

| D02 |

6.18 |

4.54 |

4.08 |

| D03 |

6.47 |

4.50 |

3.64 |

| D04 |

6.58 |

4.69 |

4.27 |

| D05 |

6.80 |

4.83 |

4.37 |

| D06 |

7.28 |

4.96 |

|

| D07 |

6.76 |

5.45 |

|

| D08 |

6.66 |

5.19 |

|

| D09 |

7.25 |

5.90 |

|

| D10 |

6.23 |

4.46 |

|

Of note: the scientific impact of the CRCs decreased between the pre-award and supported periods, but it remained far above the world level. The scientific impact of the control group also decreased, but to a lower extent than that of the CRCs. Therefore, no positive effect of the program could be observed in terms of the scientific impact of CRCs.

Overall, the findings from the bibliometric study show that the CRCP nomination, review and selection processes help to ensure that higher quality (or excellent) researchers receive the award. The study also shows that researchers continue to be excellent (as measured through publications) following the receipt of their CRC award and suggests that the CRC award contributes to increased rates of publication. Although a decrease in scientific impact was found in comparison to the control group, the scientific impact of CRCs following the award remained above the world level. These findings are similar to those from the bibliometric studies completed for the last two evaluations of the CRCP, which continue to validate these processes.

“For my renewal we compared my H-Index and citations from [before] to now and there is an enormous quantifiable impact on [my] research outputs.”

—CRC

Many CRCs who participated in the case studies confirmed the bibliometric findings by sharing that their CRC award helped increase their publication rates by increasing their profile and opportunities to collaborate. Some CRCs also perceived the award, particularly its prestige, as having an impact on the calibre of journals in which their research is published, and they found they had further reach to publish in more journals.

Research publications by institution size and CRC Tier

As part of the bibliometric study, the publication rates of CRCs were examined across institution size and by CRC Tier. Some of the key findings from this analysis include an observed higher average number of publications for CRCs working in medium and large institutions, compared to CRCs working in small institutions. These findings align with results of the CRC survey, which show that CRCs working in large institutions reported publishing more refereed journal articles (mean = 18.6) than CRCs working in medium (mean = 12.6) and small institutions (mean = 9.9). The differences in publication rates may be because CRCs located at medium and large institutions tended to supervise more students (mean = 11.5 students and 11.3 students, respectively) than CRCs in small institutions (mean = 8.4 students). Additionally, large and medium institutions are more likely to have a higher proportion of Tier 1 CRCs (39% and 33%) than small institutions (16%). According to the CRC survey, Tier 1 CRCs (on average) tend to publish more refereed journal articles (mean = 20.8 articles) than Tier 2 CRCs (mean = 13.4 articles). The bibliometric study also found that Tier 1 CRCs had higher publication rates than Tier 2 CRCs in all research disciplines.

Alternative metrics

The three granting agencies have acknowledged that traditional notions of research excellence such as bibliometrics can result in biased research assessment, which subsequently impacts funding decisions. It is well documented in the literature that typical research indicators (e.g., citation and impact factors) can be discriminatory (Davies et al., 2021). As a formal commitment to evolving the definition of research excellence, the agencies (alongside CFI) have all signed DORA. In seeking an evolved definition of research excellence, the agencies have identified diversity as a criterion of research excellence. This requires achieving a broader disciplinary mix of researchers across fields and fostering a culture of excellence in knowledge creation and translation. This new approach to interpreting research excellence will recognize fundamental knowledge creation, knowledge mobilization, multiple ways of knowing, and non-traditional research methodologies and outputs as cornerstones of Canadian research.,,

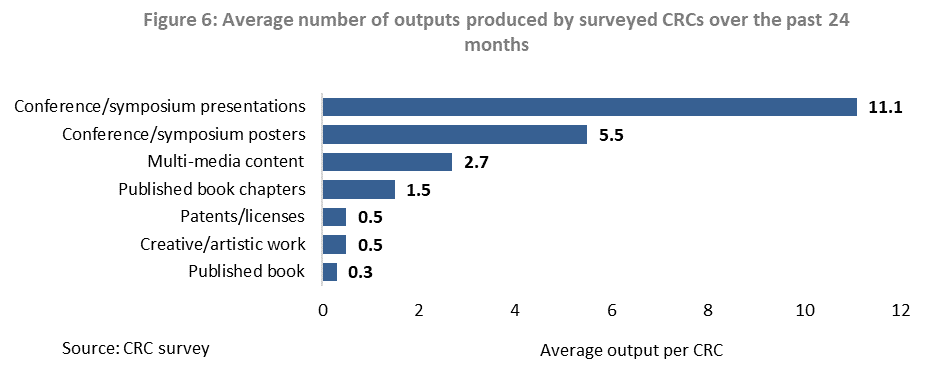

Looking at alternative metrics, such as social media, book chapters, patents and policies, the altmetric study found that CRCs increased their presence in wider audience media (e.g., Facebook, Twitter and news media) before and after receiving their CRC award. The increase in Twitter mentions was the most significant, particularly for CIHR-funded CRCs, where there was a 47% increase. However, the share of publications by CRCs that were cited in Wikipedia decreased during the award period. The CRC survey also asked CRCs to indicate the number of alternative metric outputs they generated over the past 24 months (see Figure 6). The most common outputs were conference/symposium presentations (average of 11.1 per CRC), followed by conference/symposium posters (average of 5.5 per CRC), multimedia content (average of 2.7 per CRC) and published book chapters (average of 1.5 per CRC). These findings align with the information provided by CRCs through the case studies, specifically that the CRC award helped them to generate research outputs such as presentations at national and international conferences.

Description of figure

Figure 6: Average number of outputs produced by surveyed CRCs over the past 24 months

| Outputs |

Average output per CRC |

| Published book |

0.3 |

| Creative/artistic work |

0.5 |

| Patents/licenses |

0.5 |

| Published book chapters |

1.5 |

| Multimedia content |

2.7 |

| Conference/symposium posters |

5.5 |

| Conference/symposium presentations |

11.1 |

Source: CRC Survey

With very small differences observed between CRCs and the control group, the altmetric study could not confirm that the CRCP had a clear positive effect on the inclusion of research generated by CRCs in social media. The only exception were SSHRC-funded CRCs who experienced a higher increase in the number of Twitter mentions related to their research, as compared to the matched control group (a difference of 3%). While there were little differences between CRCs and the matched control groups in terms of the presence of their research in social media, CRCs did outpace unsuccessful nominees across all disciplines, with the exception of citations in Wikipedia.

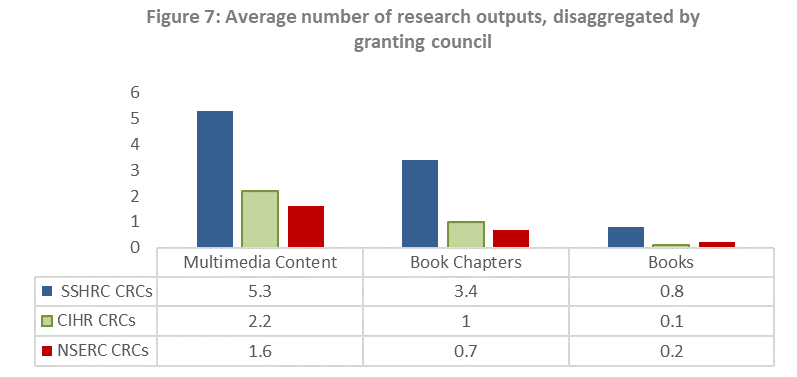

Looking at survey findings about research outputs across granting agencies (see Figure 7), SSHRC-funded CRCs produced, on average, more multimedia content, book chapters and books (mean = 5.3, 3.4, and 0.8, respectively) than CIHR-funded CRCs (mean = 2.2, 1.0, and 0.1) and NSERC-funded CRCs (mean = 1.6, 0.7, and 0.2).

Source: CRC survey

Source: CRC survey

Description of figure

Figure 7: Average number of research outputs, disaggregated by granting council

| Granting Council |

Research Outputs |

| Average number of multimedia content produced by CRCs |

Average number of book chapters produced by CRCs |

Average number of books produced by CRCs |

| SSHRC |

5.3 |

3.4 |

0.8 |

| CIHR |

2.2 |

1 |

0.1 |

| NSERC |

1.6 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

Source: CRC Survey

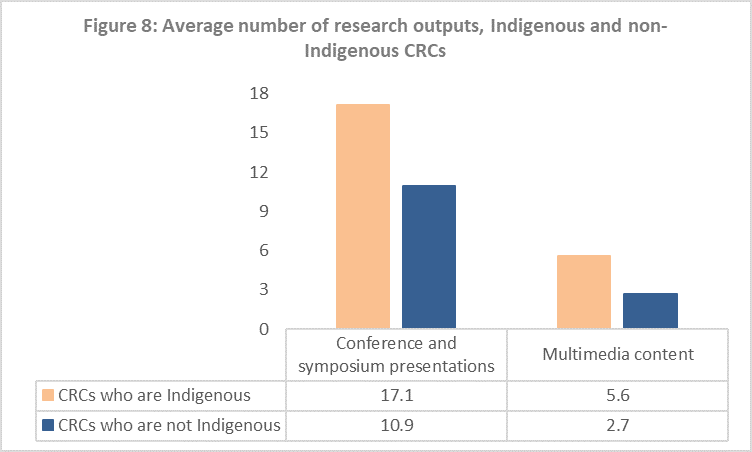

Figure 8 shows that surveyed CRCs who are Indigenous produced, on average, more conference and symposium presentations (mean = 17.1) than CRCs who are not Indigenous (mean = 10.9) and more multimedia content (mean = 5.6) than CRCs who are not Indigenous (mean = 2.7).

Source: CRC survey

Source: CRC survey

Description of figure

Figure 8: Average number of research outputs by Indigenous and non-Indigenous CRCs

| |

Research Outputs |

| Average number of conference and symposium presentations by CRCs |

Average number of multimedia content produced by CRCs |

| CRCs who are Indigenous |

17.1 |

5.6 |

| CRCs who are not Indigenous |

10.9 |

2.7 |

Source: CRC Survey

During the award period, the citation rates of the research produced by CRCs decreased in policy documents and patents. This may be attributed to the fact that these citation types require more time to mature. With very small differences observed between the citation rates of CRCs and the control group, the altmetric study could not confirm that the CRCP had a clear positive effect on the inclusion of research produced by CRCs in policy documents and patents. The study did uncover a difference in the rate of citations of CRCs and unsuccessful nominees within patents, with unsuccessful nominees being cited more often. The reasons for this difference are unknown.

Knowledge sharing and translation

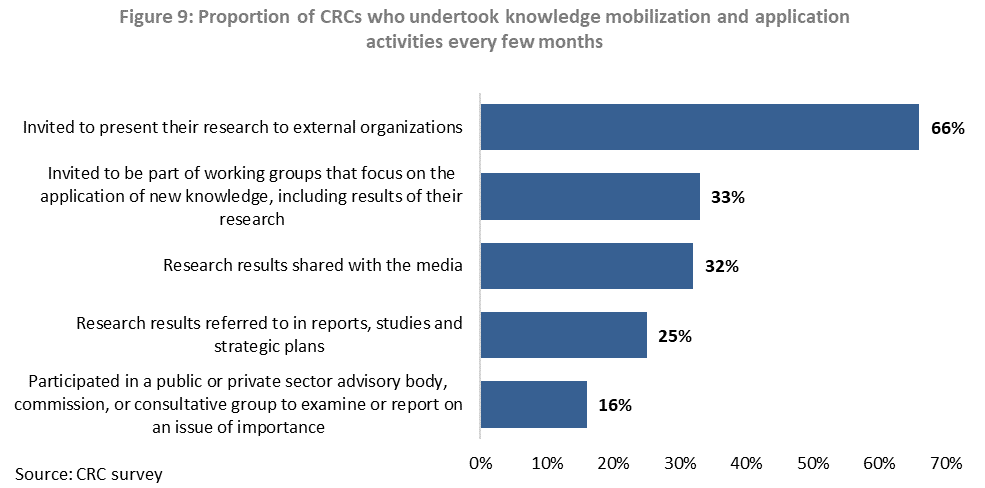

CRCs often engage in a variety of knowledge translation activities to communicate the insights and findings from their research with audiences outside academia. Data from CRC annual reports show that, between 2015 and 2020, almost all CRCs (89%) indicated that they engaged in knowledge translation “frequently” (47%) or “occasionally” (42%). When CRC survey respondents were asked how often they were invited to engage in various knowledge-sharing activities outside of academia, the most common activities reported were presenting their research to external organizations (66%); participating in working groups that focus on the application of new knowledge, including the CRCs’ research (33%); and sharing with the media (32%). Fewer respondents reported that their research results were referred to in reports, studies and strategic plans (25%), or that they participated in a public or private sector advisory body, commission or consultative group to examine or report on an issue of importance (16%). These data are represented in Figure 9.

Description of figure

Figure 9: Proportion of CRCs who undertook knowledge mobilization and application activities every few months

| Knowledge translation activities |

Percentage of CRCs who engaged in each knowledge translation activity |

| Participated in a public or private sector advisory body, commission or consultative group to examine or report on an issue of importance |

16% |

| Research results referred to in reports, studies and strategic plans |

25% |

| Research results shared with the media |

32% |

| Invited to be part of working groups that focus on the application of new knowledge, including results of their research |

33% |

| Invited to present their research to external organizations |

66% |

Source: CRC Survey

The CRC survey also provided evidence that the research produced by CRCs contributed to developing or improving government (47%), not-for-profit (43%), private company (42%) and community-based (38%) processes, policies and products. When examined across the granting agencies, the data demonstrate that SSHRC-funded CRCs were more likely to indicate that their research contributed to developing or improving government, not-for-profit and community-based processes, policies and products every few months; NSERC-funded CRCs were more likely to indicate that their research frequently contributed to developing or improving private company processes, policies and products.

“Canada benefits from having experts in the field weighing in on policy and geopolitical issues.”

—CRC

Several of the CRCs who participated in the case studies discussed the ways in which their research was shared outside of academia. These were similar to the findings from the previous CRCP evaluation; for instance, being called on by media to provide interviews, press releases, commentary or opinion articles, and to provide expert advice. In some cases, CRCs consulted and produced reports for federal departments such as Statistics Canada, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, or the Department of Canadian Heritage; provincial government departments (e.g., ministries of health) and agencies; and government science centres. As for the private sector, CRCs provided examples of consulting with and advising industry stakeholders, as well as sitting on advisory boards.

4.2 Collaborations

The CRCP had a positive impact on the number and quality of research collaborations for CRCs with researchers working at the same institution, other national institutions or international institutions. The award helped strengthen existing collaborations and provided opportunities to network and develop connections that resulted in collaborations. According to annual report data, CRCs were more likely to collaborate with researchers within their own institution. This is in line with findings from the bibliometric study, where CRCs increased their rate of national and institutional co-publication at a higher rate than a similar set of non-CRC researchers, perhaps as a result of CRCs becoming part of research clusters at their institutions or across Canadian institutions following their CRC award. CRCs also increased their rate of international co-publication following the award, but not at the same rate as a similar set of non-CRC researchers.

More than three-quarters of surveyed CRCs (78%) reported a positive impact on the quality of their collaborations as a result of their CRC award.

Almost all institutional representatives agreed that the CRC award had a positive impact on the number of research collaborations (90%) and the quality of the research collaborations at their institution (88%). At the individual level, most CRC survey respondents (78%) reported that the CRC award had a positive effect on the quality of their research collaborations. This positive impact was also noted by almost all interviewed CRCs, who described an increase in the quality or quantity of their research collaborations since receiving their award. They often attributed this to the prestige associated with the CRCP. The award was perceived to have helped strengthen pre-existing collaborations more so than facilitating the development of new ones. CRCs also provided examples of international and national researchers reaching out to them to collaborate on research projects, as well as receiving positive responses to their own requests to collaborate with international and national researchers. Being recognized as a CRC was perceived as a mechanism for increasing opportunities to attend and present at events, ultimately resulting in more chances to network and develop collaborations. Additionally, researchers often received protected time that released them from teaching and administrative responsibilities, as well as some supplementary funding when they became a CRC. They noted this provides them with more time to focus on developing their collaborations, including travelling to work with collaborators, subsequently allowing them to expand their research capacity.

“Certainly, the title helps with establishing collaborations, there is no question.”

—CRC

Data extracted from the CRC annual reports show that a large majority of CRCs (88%, similar to the previous evaluation’s 87%) had significant collaborations with researchers within their own institution, which included building research clusters with their colleagues to help each other apply for grants, share equipment and fund HQPs. It is possible that these collaborations existed before the CRCs received their award and may be why the award was perceived to help strengthen pre-existing collaborations About 70% (similar to the previous evaluation’s 68%) of CRCs also reported having significant collaborations with international institutions, and more than half (58%, similar to the previous evaluation’s 56%) of CRCs collaborated significantly with researchers at other Canadian institutions. CRCs provided examples of leading national research networks; participating in, advising or leading international research organizations; or collaborating with specific researchers and teams at other institutions. When asked about the types of collaborations they were involved with as part of their research, internationally recruited CRCs reported more frequent and significant collaborations with researchers working at international institutions (77%), compared to CRCs who were recruited from the host institution (70%) and those recruited from another Canadian institution (51%). Additionally, Tier 1 CRCs (78%) were more likely to report collaborations with researchers at international institutions than Tier 2 CRCs (63%).

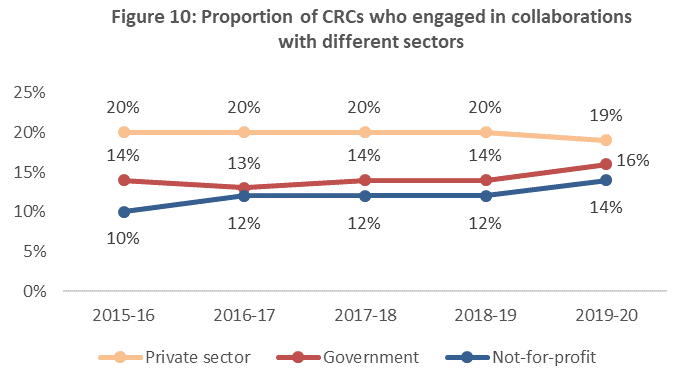

The CRC annual reports further demonstrate the extent to which CRCs engaged in national and international private sector, government and not-for-profit collaborations. Overall, about a fifth (20%) of CRCs collaborated significantly with the private sector in Canada, while a small proportion collaborated significantly with government (14%) and not-for-profit organizations (12%). Figure 10 shows that the trend of these collaborations remained fairly consistent between 2015-16 and 2019-20. At an international level, these percentages decreased to 3% of CRCs reporting significant collaborations with the private sector, while just under one-tenth of CRCs (9%) reported engaging in significant collaborations with international governments or not-for-profit organizations (8%). Some CRCs who participated in the case studies reported having significant national and/or international collaborations with different sectors. Examples of such collaborations included advising private and not-for-profit organizations, as well as collaborations with community groups, initiatives and organizers.

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Description of figure

Figure 10: Proportion of CRCs who engaged in collaborations with different sectors

| Year |

Sector |

| Private sector |

Government |

Not-for-profit |

| 2015-16 |

20% |

14% |

10% |

| 2016-17 |

20% |

13% |

12% |

| 2017-18 |

20% |

14% |

12% |

| 2018-19 |

20% |

14% |

12% |

| 2019-20 |

19% |

16% |

14% |

Source: CRC Annual Reports

Co-publication rates

The bibliometric study examined co-publication rates for CRCs before and during their award, as well as for a matched control group and unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP. International, national and institutional co-publications were reviewed as part of this analysis as a proxy measure for collaborations. The bibliometric study also examined single-author publication (i.e., the CRC or matched researcher was the sole author). As these indicators are mutually exclusive, when the rate of one type of publication increased it was expected that the rates of other types of publications would concomitantly decrease.

Before their award, CRCs had higher international co-publication rates than the control group. However, their national-only and institutional-only (local) co-publication rates were similar or lower. Overall, CRCs increased their rate of international co-publication following their award by 12 percentage points. However, researchers in the control group demonstrated higher rates of international co-publication than CRCs during the latter group’s award period. This was counterbalanced by CRCs faring slightly better than the control group during their award period in terms of national and institutional co-publication. Although not confirmed by the evidence, it could be presumed that CRCs have increased their national and institutional co-publication versus international co-publication more than the matched control group because many of the CRCs were part of research clusters at their institutions and across Canadian institutions (as noted in Section 3 above).

The rates of single-author publication were very similar for CRCs funded by CIHR or NSERC and their counterparts in the matched control group during the CRC’s award period. However, CRCs funded by SSHRC experienced a decrease in their share of single-author publication compared to their control group. These findings suggest that the CRCP had a greater positive effect on the chances of SSHRC-funded CRCs to participate in collaborations resulting in co-publication. The beneficial effect appears mostly at the national and institutional levels. The larger proportion of SSHRC-funded CRCs working at small institutions may also explain why CRCs at small institutions had higher rates of co-publication and fewer single-author publications.

Overall, unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP did not progress in the same way as the CRCs with respect to collaborations when measured by co-publication rates. In particular, CIHR-funded Tier 2 CRCs had higher rates of international co-publication and SSHRC-funded Tier 2 CRCs had higher rates of institutional co-publication compared to their unsuccessful nominee counterparts. Moreover, the rate of single-author publication from unsuccessful nominees did not decrease to the same extent as they did for the SSHRC-funded Tier 2 CRCs with whom they were matched, suggesting that unsuccessful nominees experienced fewer opportunities to engage in collaborations that resulted in co-publication.

Connecting with other CRCs

A suggestion offered throughout the evaluation in support of collaborations was to have an annual conference / meeting for CRCs. This would create networking opportunities, would allow CRCs to learn about what others were working on at different institutions and help identify potential opportunities for collaboration. It would also provide opportunities for CRCs to share some of their challenges and lessons learned, and to compare their situations, including the support received by their institutions (discussed further in Section 7.7). It was also felt that such gatherings, even though virtual, would have been helpful during the pandemic. There were also perceived opportunities to bring together smaller groups of CRCs working in similar research areas for more focused networking opportunities; for instance, CRCs working with Indigenous communities.

4.3 Cross-disciplinary research

Cross-disciplinary research (interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary) is an important consideration for the CRCP and institutions as, according to the literature, it is expected to result in more durable socio-economic change.

Interviewed CRCs perceive increased opportunities for cross-disciplinary research and most CRCs surveyed reported that the CRC award increased their participation in multidisciplinary (74%) and interdisciplinary (73%) research collaborations. Cross-disciplinary scores of CRCs were close to or higher than the world level before receiving their CRC award, indicating that the CRCP was successful in attracting world-class researchers who engaged in disciplinary diversity. However, there was no overall measurable effect of the program on the cross-disciplinarity of research conducted by CRCs. Following the award, the level of interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity among all CRC publications reduced slightly. When compared to the control group, the bibliometric analysis shows that, overall, CRCs fared slightly better than the control group on cross-disciplinary dimensions, but unsuccessful nominees to the CRCP performed slightly better than CRCs on most cross-disciplinary dimensions.

The evaluation also found that while some institutions seem able to use their CRC awards to create interdisciplinary faculty positions, other institutions found the CRCP limiting in this respect, particularly if the disciplines crossed granting agency disciplinary boundaries. As CRC awards are associated with a specific agency, some key informants and case study participants perceived that they can create a siloed nomination process that may not support interdisciplinary researchers. It was also perceived that interdisciplinary nominations can pose challenges during the peer review and that nominations may be sent back to the institution with questions or requests for additional information.

Research that crosses disciplinary and sectoral boundaries is expected to result in more durable socio-economic change., A review of the Strategic Research Plans of the 10 case study institutions reveals the prioritization of interdisciplinary and/or multidisciplinary research, often in areas with one or more CRCs. Also, some of the case study institutions are focusing on developing interdisciplinary research teams and are using their CRC awards to create interdisciplinary faculty positions and attract interdisciplinary researchers. In certain cases, CRCs noted that the interdisciplinarity of the CRC position is what drew them to apply, as much if not more than the fact that the position was tied to the CRCP.

In contrast, some key informants and case study participants believe that the CRCP is not currently designed to support interdisciplinary research positions. The main limiting factor highlighted was that CRC awards are associated with a specific agency, creating a siloed nomination process that does not support interdisciplinary researchers. Some case study participants highlighted the difficulty experienced by interdisciplinary nominees: they felt that the researcher needed to adjust their research program as described in their nomination package to favour one discipline over another to fit within agency-specific funding requirements. A few key informants also highlighted that the peer-review process is sometimes challenged when nominations reflect interdisciplinary research: this has resulted in nominations being returned to the institutions with questions or requests for more information. Consequently, there is a question as to whether the design of the CRCP’s nomination and review processes disadvantaged interdisciplinary researchers.

After receiving the award, however, interviewed CRCs reported that it increased their opportunities for cross-disciplinary research (i.e., interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary). Most surveyed CRCs noted that the award increased their participation in multidisciplinary research collaborations (74%) and interdisciplinary research collaborations (73%). The bibliometric study examined cross-disciplinary indicators to assess the extent to which the program awarded CRC positions to researchers involved in cross-disciplinary research and changes in the rates of cross-disciplinary research following the award. Before receiving their award, CRCs were at par overall with the world average in terms of interdisciplinarity and close to the world average for their share of publications among the 10% most highly interdisciplinary publications. While Tier 2 CRCs were slightly higher than the world average when it came to interdisciplinarity, Tier 1 CRCs were close to or slightly lower than the world average. Moreover, CRCs were higher than the world average in terms of multidisciplinarity; CIHR-funded CRCs had particularly high values compared to the world average. SSHRC-funded CRCs specifically stood out for their high level of interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity based on their publications before receiving their CRC award. Of note, the interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity publications of unsuccessful SSHRC Tier 2 nominees before their nominations were higher than the world level and above Tier 2 CRCs from all agencies.

During the award period, the level of interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinarity among all CRC publications decreased slightly. When examining specific groups of CRCs, these reductions were mainly attributed to observed decreases in the interdisciplinarity of publications from NSERC-funded CRCs. In comparison, SSHRC-funded CRCs slightly increased their share of publications among the most interdisciplinary publications in the world. In the case of multidisciplinary publications, SSHRC-funded Tier 2 CRCs increased their share of such publications, but SSHRC-funded Tier 1 CRCs had the largest decreases of all CRCs in terms of multidisciplinarity exhibited in their publications, as well as their share of the 10% most multidisciplinary publications.

When compared to the matched control group, the bibliometric analysis shows that CRCs fared slightly better than the control group on cross-disciplinary dimensions. These differences were very small and hard to validate for the overall sample of CRCs. However, when disaggregated by group, the analysis was able to show with more confidence that SSHRC-funded Tier 2 CRCs performed better than their matched counterparts in terms of the level of interdisciplinarity exhibited in their publications, as well as their share of the 10% most multidisciplinary publications. CIHR-funded CRCs performed better than the control group for their share of papers among the most interdisciplinary.

The bibliometric study further shows that unsuccessful CRCP nominees performed slightly better than CRCs on most cross-disciplinary dimensions. For instance, the average level of interdisciplinarity or multidisciplinarity exhibited in unsuccessful nominees’ publications continued to increase compared to the world average: this was not the case for CRCs except for SSHRC-funded Tier 2 CRCs. Additionally, the unsuccessful nominees’ share of publications among the 10% most multidisciplinary publications increased more than those of CRCs. However, CRCs performed better than unsuccessful nominees in increasing their share of publications among the world’s most interdisciplinary publications.

4.4 Students

In addition to CRCs, students supervised by CRCs reported that they benefitted from the CRCP. According to annual reports, CRCs believe that the prestige of being a CRC helped them attract more high-calibre students (Canadian and international) to their research program. It also significantly enhanced their ability to provide training. During interviews, students were positive when discussing their experience working with a CRC. In a survey of students, those supervised by CRCs identified having greater opportunities than non-CRC supervised students in the following areas:

- practicing technical research skills, non-technical skills and professional skills;

- participating in a variety of knowledge dissemination activities, such as preparing papers, presentations, communications, grant proposals, conferences and workshops;

- training on new equipment, formal or informal specialized training, as well as opportunities to participate in events or activities that have the potential to expand their network of potential employers; and

- opportunities to participate in collaborations.

According to the CRC annual reports, CRCs directly supervised an average of eight students at a time, most of whom were graduate students and one to two postdoctoral researchers. Additionally, they co-supervised approximately two students and sometimes a postdoctoral researcher. When asked about the extent to which their position (including associated CFI funding) enhanced the training they could provide to the students and research staff, CRC annual reports showed that most CRCs (76%) indicated that being a CRC significantly enhanced their ability to provide training.

CRCs reported that the award helped them attract more students to their research program, including more high-calibre national and international students. Results from the survey show that most CRCs indicated that their position increased their ability to attract more students and research staff (82%), as well as attract higher-quality students and research staff (73%). While many interviewed CRCs noted that they were able to leverage their position to attract students, they experienced some challenges engaging students because of a lack of available funding or the inadequate amount offered to students through research stipends. It was noted that the stipends for students were low and often not enough to keep up with the increasing cost of living. In one case, it was further noted that CRCs sometimes missed opportunities to hire the “best” students because the stipend amounts were too low. Studies have shown that financing is a crucial factor in attracting and retaining international students and that there has been a global loss in international student recruitment in academia. These studies partially attributed this to a lack of investment in this area. On average, approximately 4% of CRCP funding was used to fund students. In most cases, CRCs were required to seek additional funding to supplement their research budget for students.

Interviewed CRCs noted that they recruit students through a variety of methods, including online listings (e.g., LinkedIn, institution’s website, job boards), informal networking and peer recommendations, as well as being directly solicited by students interested in working with them. Nearly all interviewed CRCs mentioned taking deliberate action to integrate EDI practices into their hiring processes to support working with a more diverse group of students. Such actions include taking courses to better understand diversity, looking specifically for members of EDI groups when hiring, and taking steps to make all students feel welcomed despite language and cultural barriers. According to some CRCs, it is important to hire students from diverse backgrounds—academic and identity—as diversity supports successful research with opportunities to bring in different perspectives and ideas. More than half (55%) of the surveyed CRCs agreed that being a CRC increased their ability to attract students and research staff who belong to one of the CRCP’s designated groups.

Students who participated in the case studies described the activities and opportunities available to them when working with a CRC, such as:

- participating in data collection and analysis, literature and document reviews, and coding analysis;

- access to specialized labs and equipment, including specialized equipment training;

- participating in theoretical research;

- participating in national and international research collaborations and partnerships;

- attending conferences;

- presenting at events; and

- supporting the development of research publications and co-authoring.

CRC-supervised students surveyed reported having more opportunities than non-CRC-supervised students to practice technical research skills, non-technical skills and professional skills. CRC-supervised students also reported greater opportunities to participate in a variety of knowledge dissemination activities, such as preparing papers, presentations, communications, grant proposals, conferences and workshops. Additionally, as a trainee being supervised by a CRC, students received more training on new equipment, formal or informal specialized training, as well as opportunities to participate in events or activities that have the capability of expanding their network of potential employers.

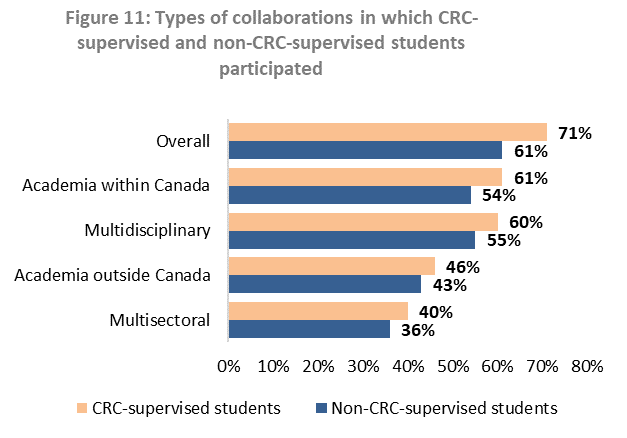

Evidence from the student survey also showed that more CRC-supervised students reported having an opportunity to participate in collaborations (71%) compared to non-CRC-supervised students (61%). Furthermore, CRC-supervised students reported a higher frequency of collaborations, whether multidisciplinary, multisectoral, or with researchers from academia within and outside of Canada, compared to other students (see Figure 11). CRC-supervised students interviewed as part of the case studies confirmed that their work with CRC resulted in participation in national and international research collaborations and partnerships.

Source: NSERC-SSHRC Talent Survey

Source: NSERC-SSHRC Talent Survey

Description of figure

Figure 11: Types of collaborations in which CRC-supervised and non-CRC-supervised students participated

| Types of Collaborations |

Student Groups |

| Non-CRC-supervised students |

CRC-supervised students |

| Multisectoral |

36% |

40% |

| Academia outside Canada |

43% |

46% |

| Multidisciplinary |

55% |

60% |

| Academia within Canada |

54% |

61% |

| Overall |

61% |

71% |

Source: CRC Annual Reports

“I want to be a scientist and I am learning how to be a scientist. I have gotten some hands-on skills in terms of working with wildlife. I had never worked with mammals before. Now, I have experience working with mammals, GPS collars, data from collars, audio recorders.”

—CRC Supervised Student

Interviewed students were nearly all positive when discussing their experience working with a CRC. They often praised their supervisor’s personal qualities, such as their passion for work, empathy, knowledge and expertise, or friendliness. Some students also mentioned benefitting from their supervisor’s leadership skills, such as lab management, grant writing, communication and independence. In certain cases, students experienced longer-term positive impacts, noting that their subsequent career and research opportunities benefitted from the training and experience gained working with the CRC. These included awards, tenure-track positions and ivy-league postdoc positions. Such assertions were supported by interviewed CRCs who noted that opportunities to work on their research program has led to students receiving prestigious positions of their own, including high-level positions within large research projects, Tier 2 CRC positions and top prizes for graduates.

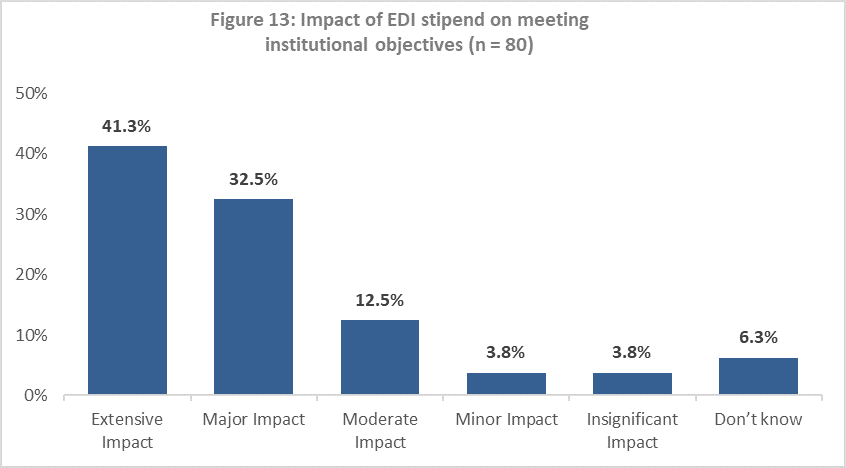

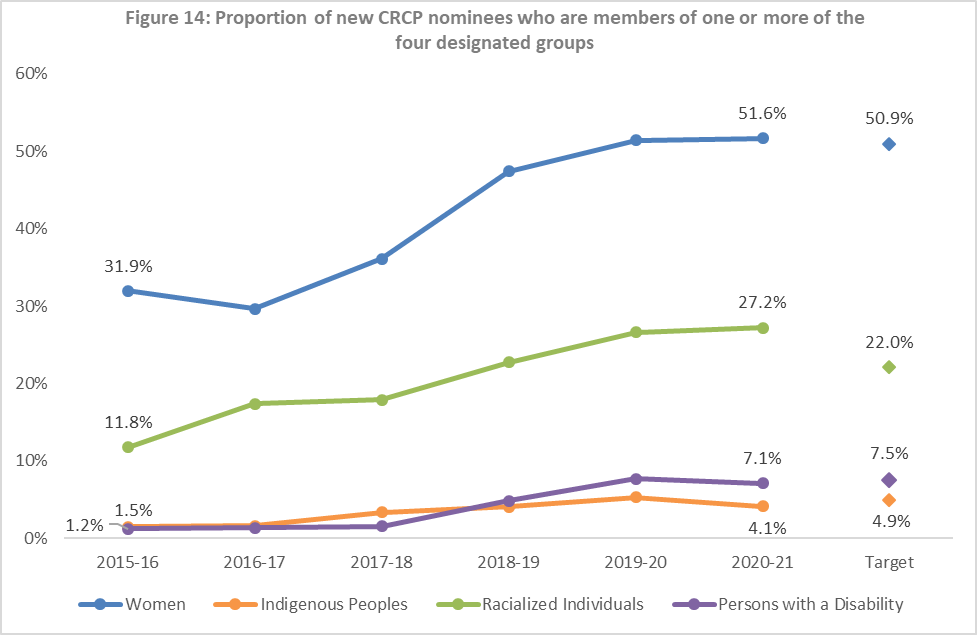

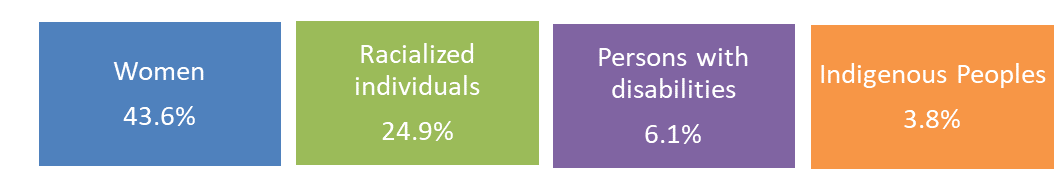

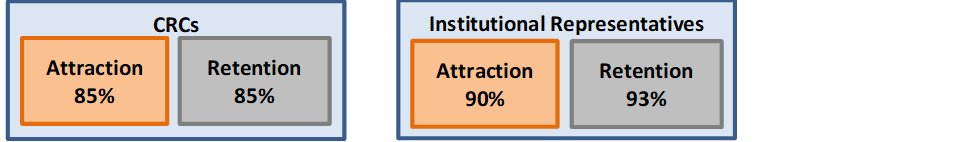

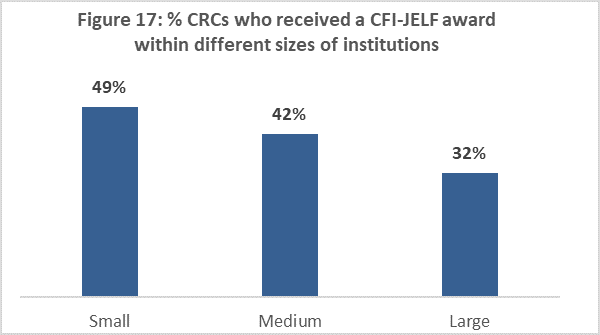

4.5 COVID-19